Bubble Barriers are effective tools for catching plastic pollution in rivers. After removing the plastic waste from waterways, we are able to closely sort and monitor the catch. The collected data provides us with valuable insights into the levels of pollution in these rivers. And it also helps prevent plastic from ending up there in the first place.

Author: Teagan Prawmanee Intaralib

Editor: Judith de Waard

Plastic Monitoring: Why it’s Important

Plastic pollution in rivers is a complex problem with many different factors at play. For us to understand the issue, monitoring is a vital tool. Eventually, these insights help tackle the problem close to the source.

Here’s one example of how plastic monitoring made a real change: the cough drop company Anta-Flu changed their wrappers from plastic to paper after a push from active Dutch citizen scientists, backed by over 30,000 data entries of plastic wrappers found and monitored. Systemic monitoring ensures useful and comparable data while it also supports the decision-making process in water-related policies.

How Do We Set Up Monitoring for Our Plastic Pollution Catch?

For each Bubble Barrier location, we identify the steps needed to start monitoring the local catch. In some locations, that includes supporting local citizen initiatives with the tools to conduct plastic monitoring. In others, monitoring is done by an external research institute.

To systematically monitor the plastic catch per location, the Bubble Barrier catchment system is emptied on a regular schedule. Each ‘batch’ of plastic waste gets collected in big bags. First, the waste is left to dry for a few weeks to prevent the data from being skewed by the water weight.

Once the catch is dried, organic waste, such as branches or leaves, is separated and removed from the total catch. Organic materials are not included in the monitoring.

Then the nitty gritty work begins: we sort, weigh, and categorise the waste according to the river-OSPAR method.

What is the OSPAR Method?

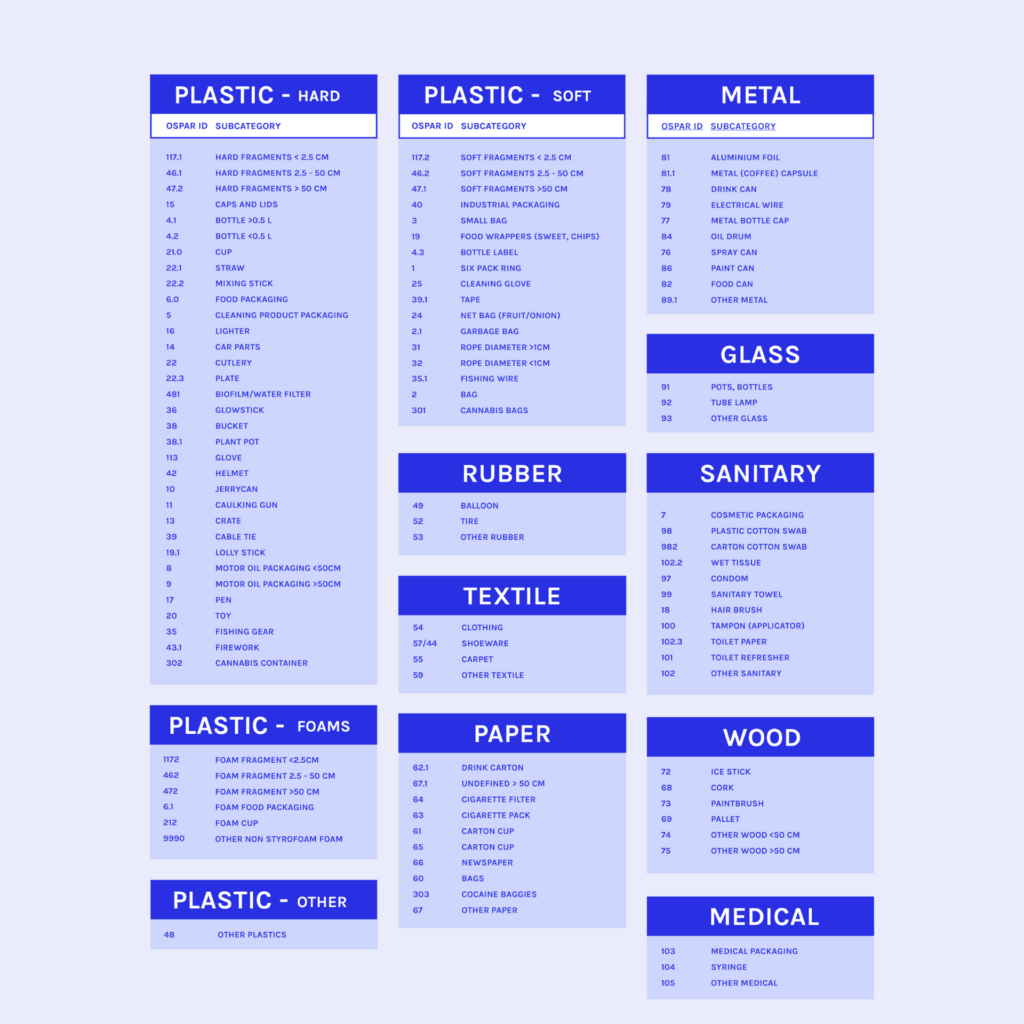

OSPAR, named after the Oslo and Paris conventions, is a cooperation mechanism between 15 governments and the EU to protect the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic. Their OSPAR methodology for monitoring plastic waste acts as the international standard.

The official OSPAR guideline was first introduced to focus on monitoring beach marine litter. It contains over 100 subcategories of waste types and a comprehensive methodology for identification and data collection.

Based on the original protocol, the river-OSPAR protocol was then later developed by Stichting De Noordzee to monitor waste found along the Dutch riverbanks. The detailed categorisation allows the collection of standardised and comparable data between different locations that are monitoring plastic pollution in rivers.

Categorising Plastic

Within river-OSPAR, there are twelve main material categories, such as plastic foams, soft plastic, sanitary, rubber, and textile. Those are split out into 106 specific object categories, such as ‘cigarette filters’, ‘food wrappers’, or ‘balloons’. Once categorised, the pieces of waste are counted and weighed.

All the collected data helps us understand river plastic pollution trends in specific areas. For example, to identify the kind of industry waste that ends up in the water, or where certain food packaging comes from.

Challenges in the Monitoring Process

Despite the many categories offered in the river-OSPAR method, no monitoring methodology is ever perfect. For example, plastics that have become fragmented in water are difficult to determine and put into the right category.

Also, some items, such as drink cartons and cigarette filters, are categorised under ‘paper’, when they contain plastic, which can skew our perception of the results. Regardless of these challenges, OSPAR is an invaluable tool in our journey to better understand plastic pollution in rivers.

What Does the Bubble Barrier Catch?

The items collected by our Bubble Barriers vary greatly, ranging from plastic bottles and metal cans to books, toys, and even Christmas trees. The Bubble Barrier is effective at catching small microplastics from 1 millimetre, like styrofoam, as well as larger items such as surfboards. Our Impact Researcher, Finn Begemann, mentioned in an interview that the strangest item caught to this day was a plastic dildo, which is still displayed at the office.

Monitoring Results: Bubble Barrier Amsterdam

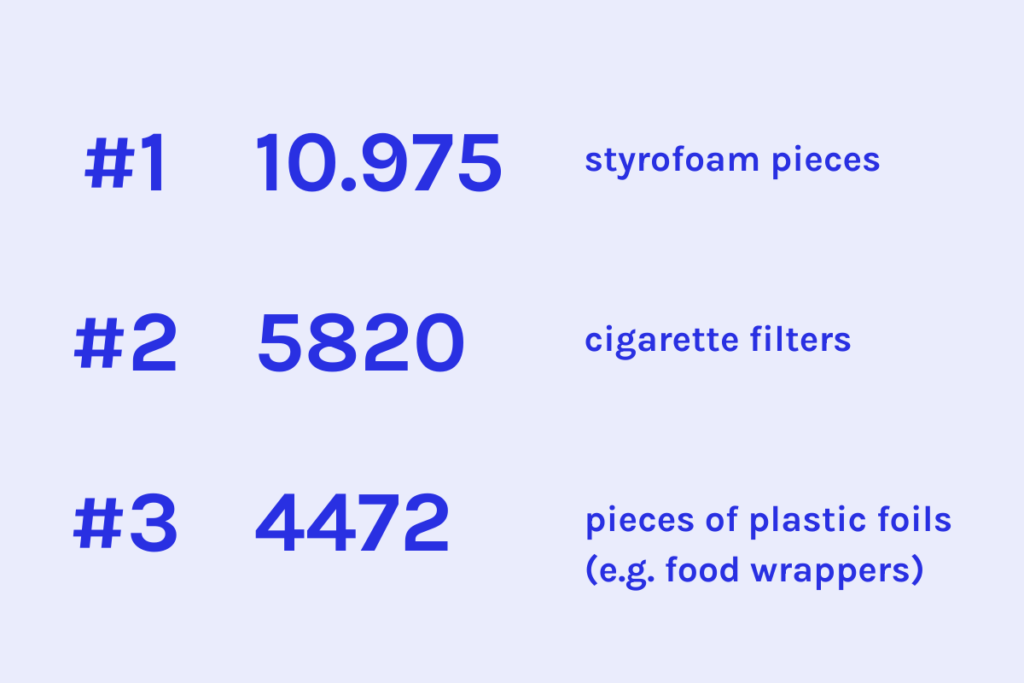

In 2021, we conducted one year of research on the plastic catch of Bubble Barrier Amsterdam in collaboration with the Plastic Soup Foundation.

Over one year, a total of 38,178 pieces of dried, inorganic waste, weighing over 208 kilogrammes combined, were monitored. After sorting the catch into the twelve main OSPAR categories, we observed that the most common material found – over 71% – was plastic. The most common items found in Amsterdam are styrofoam pieces, cigarette filters and pieces of plastic foil.

Curious to find out more about our monitoring results in Amsterdam? Read more about Bubble Barrier Amsterdam’s impact here.